For just over the last week I have been struggling to sit down and write, it’s one those moments that I just can’t think of anything constructive to say. It’s is linked to the fact that twitter keeps throwing up interesting people and blogs concerned with psychogeography and I’m hit by the amount of really exciting work that is already happening and I’m struck with doubt in the validity of what I’m doing and trying to say.

This would no doubt of been helped if after last weeks time spent in the Thames Gateway I had been able to develop my films and hold a tangible piece of research. However film as I am readily reminded by everyone (especially while out in the field trying to explain what a large format camera is) is a dying entity, and increasingly difficult to get commercially developed. While my local Snappy Snaps is able to run 120 through their machines in an hour, I am very reticent to trust their level of service. So instead I either have to use uni or Metro in London, the downside to this is I have to wait until either I am visiting London for a meeting, or have enough film to make the trip financially worth while.

In an attempt to kick-start some ideas again, I have been going through old notes written in my notebook and was struck by one fundamental idea; how do you define the character of a place? So welcome to what in my original plans should have been my first real post after the introduction.

First of all we have to question what place even is. To most people, at least on first thought, it is a physical geographic entity, we have to think of it like that to ground us, ‘I am here, in this place’. In this case Purfleet, opposite Feederz mini mart.

But I stop and take a breath, allowing my mind to wander, slowly I start to pick up on sounds that a few seconds ago where an ambient jumble of noise, I start to smell my surroundings. Now that place is a collection of sensory stimuli, unique to that point and time, transitory, but also a defining characteristic of the location.

As I’m setting up my camera on it’s tripod, a security guard comes over to speak to me, I’m expecting the usual hassle of trying to explain why I’m standing on a patch of grass owned by Esso, outside of the Purfleet Thames Terminal. Instead he starts to talk to me about my camera, which in turn leads to a discussion about my PhD topic. We chat for five minutes and he talks candidily about leaving Ghana to come to the UK, and having to take any job he can get as companies are worried about his foreign qualifications. Place is now about people and their stories, how they are affected by the local, regional and national (micro, meso and macro levels of analysis) socioeconomic politics.

Place is no longer a single geographic entity. To explore it we have to be open to all of these ideas.

Certainly Place is something more often sensed than understood, an indistinct region of awareness rather than something clearly defined. ‘Place’ has no fixed identity, as places themselves do not.

Place, Tacita Dean & Jeremy Miller (2005)

As a photographer, working merely on the visual senses this was something that caused me problems. In early discussions surrounding the PhD I used to joke that the easiest way of doing this work would be to take a group of people to each location and let them experience it. However I chose to go into the arts as I am interested in exploring the world and presenting my curated reading of it. There are many fine academics, sociologists, ethnographers, geographers and artists who are leading walking tours of locations, and this is brilliant, but just not for me at this moment. So how do I produce a more experiential ‘image’ of the Place.

Amy Hanley and Rick Dargavel from Manchester School of Architecture Intimate Cities, edgeland program introduced me to the work of Professor Doreen Massey and her writing on a Sense of Place, ‘First… we understand space as the product of interrelations: as constituted through interactions, from the immensity of the global to the intimately tiny… Second, that we understand space… as the sphere in which different trajectories coexist [plurality]… Third, that we understand space as always under construction.’

• places do not have single identities but multiple ones.

• places are not frozen in time, they are processes.

• places are not enclosures with a clear inside and outside.

In a Podcast interview with Social Science Space Massey talks about the idea of physical space being alive.

“A lot of what I’ve been trying to do over the all too many years when I’ve been writing about space is to bring space alive, to dynamize it and to make it relevant, to emphasize how important space is in the lives in which we live.

Most obviously I would say that space is not a flat surface across which we walk; Raymond Williams talked about this: you’re taking a train across the landscape – you’re not traveling across a dead flat surface that is space: you’re cutting across a myriad of stories going on. So instead of space being this flat surface it’s like a pincushion of a million stories: if you stop at any point in that walk there will be a house with a story.

Raymond Williams spoke about looking out of a train window and there was this woman clearing the grate, and he speeds on and forever in his mind she’s stuck in that moment. But actually, of course, that woman is in the middle of doing something, it’s a story. Maybe she’s going away tomorrow to see her sister, but really before she goes she really must clean that grate out because she’s been meaning to do it for ages. So I want to see space as a cut through the myriad stories in which we are all living at any one moment. Space and time become intimately connected.”

The idea of space and time being linked is at the heart of contemporary ‘Ian Sinclair’ psychogeography.

Sinclair’s peculiar form of historical and geographical research displays none of the rigour of psychogeographical theory and is overlaid by a mixture of autobiography and literary eclecticism… London’s topography is reconstituted through a superimposition of local and literary history, autobiographical elements and poetic preoccupations, to create an idiosyncratic and highly personal vision of the city.

Psychogeography, Merlin Coverley (2010)

This form of psychogeography and it’s issues as a sole means of research has been written about by the spatial filmmaker Patrick Kieller, famous for his Robinson trilogy of films were he knowingly subverts the educated middle class hang ups of Sinclairian psychogeography with the creation of a fictitious ‘disenfranchised, would-be intellectual, petit bourgeois part-time lecturer’.

Through the character of Robinson, Kieller is able to at times knowingly satirise the role psychogeographer as self obsessed auto ethnographer, while at the same time using the method as a means of interrogation. ‘Pschogeography was conceived, in a more politically ambitious period, as preliminaries to the production of new, revolutionary spaces; in the 1990s they seem more likely to be preliminary to the production of literature and other works, and to gentrification, the discovery of previously overlooked value in dilapidated spaces and neighbourhoods’. Ultimately highlighting the danger that all art concerned with Place can fall foul of, the danger of the artist acting as a colonialist, ‘capturing’ places that they find fascinating.

MSA’s Intimate Cities program proposed a method of research gathering to start to analyse Place; Eyewitness, Ear Witness, Interviewer, and Cartographer. It is their opinion that no one method of data gathering can explore a system as complex as the idea of Place, and it needs to be tackled through a multidisciplinary method. This is something that the traditional still image is very bad at, be it in a book or gallery wall it only offers a two dimensional representation of a multi dimensional space. For years I have struggled to come to terms with the limitations of the medium and have grown frustrated by it. Both sound arts and the moving image have been born out of collaborative practices. Combining multiple elements to give a more rounded reading of a locale.

The Sound work of Angus Carlyle in pieces such as Air Pressure (2012) and Peter Cusack’s Sounds from Dangerous Places (2012) combine photography, storytelling and psychogeographical elements in their chosen publication methods.

While the moving image work of Patrick Kieller, the Films of Saint Etienne

and the most recent documentary/ music collaboration of Karl Hyde and Keiran Evans in the project Edgelands/ The Outer Edges (2013) blend multiple disciplines to create a reading of Place.

I would argue that technology advances have allowed more photographers to start transcending the traditional boundaries of their practice, and methods of self publication have allowed them to take risks with the presentation of work that commercial galleries and book publishers would have found difficult to sell. Examples of this range From Rob Hornstra and Arnold van Bruggen’s Sochi Project, which blended photography, interviews, moving image and psychogeography to explore the complex area of the southern Russian Caucasses.

To David Dufresne & Philippe Brault’s Prison Valley (2010) which explores Cañon City, 16% of the Cañon City population is inside prison; it is an economy based almost entirely upon incarceration. Cañon City has a population of 36,000 and 13 prisons, one of which is Supermax, the new ‘Alcatraz’ of America. The new Supermax was described by former warden, Robert Hood, as “a clean version of hell.”

Purposefully designed as a web based project and “Web Documentary”. To view the film beyond its introduction you must sign in with either your Twitter or Facebook social network accounts. Once signed in the website will bounce you between a mixture of multimedia, interviews, photo-galleries, non-sequitur video clips and auxiliary documents. The documentary canvases opinion from various characters who the filmmakers meet along the way. ‘When we first started this project. We didn’t really think about shooting video. Of course, we planned to to film our interviews, but that was pretty much it. We were thinking that we would be working with photography above everything else’. World press awards judges described it in their first multimedia contest as a ‘Magnus opus visually, conceptually and in terms of the information and reporting offered’.

Both of these examples along with Karl Hyde and Keiran Evans are complemented through a strong web presence and allow the creation of interactive, explorable, curated archives.

A group from London took an alternative approach to exploring Place, Learning from Kilburn (2013-14), which they describe as:

A tiny experimental university with its curriculum rooted in Kilburn, nw6. The university will use the high road and its hinterland as a campus, occupying a number of locations for classes initially running from October 2013 to April 2014.

Weekly classes will study what makes Kilburn what it is, led by a range of artists, architects, writers and thinkers. Each class will ask a single question, looking at one thing at a time in order to understand Kilburn as a whole. The university wants to know what Kilburn looks like, where it starts and finishes, how money works in Kilburn, whether Kilburn even exists, where Kilburn is going.

Over a period of months the pop-up university has run a series of classes ranging from evening seminars, too traditional lectures, and daylong practical assignments run by collection of lecturers from differing academic and artistic backgrounds.

My practice proposes the creation of an archive of materials ranging from photography, moving image, field sound recording, and interviews as well as mapping the locales through writing. I hope like Learning from Kilburn to be able to develop the work into a wider entity and utilise the input of others into the work.

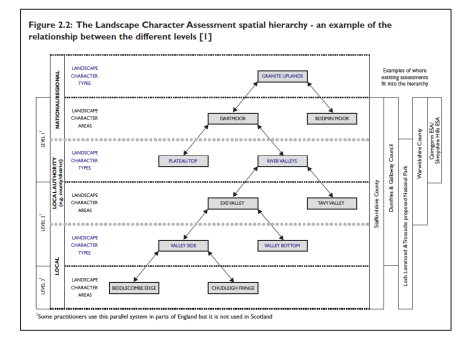

This is in conflict with the traditional architectural view of Place, which many of us can agree often has a blinkered view of the wider world that proposal inhabit. Speaking to one of my old housemates who is now a landscape architect he told me about having to perform ‘Landscape Character Assessments’ on sites during the proposal phase.

Our appreciation and understanding of landscapes have increased over time, partly as the result of our need and desire to record, understand, influence and manage change.

Landscape Character Assessment (LCA) is one tool that helps in that understanding, and is defined as:

“The tool that is used to help us to understand, and articulate, the character of the landscape. It helps us identify the features that give a locality its ‘sense of place’ and pinpoints what makes it different from neighbouring areas.”

Landscape Character Assessment: Guidance for England and Scotland, The Countryside Agency and Scottish Natural Heritage, (2002)LCA can be used in many situations, for example in devising indicators to gauge landscape change and to inform regional planning, local development, environmental assessment and the management of protected landscapes.

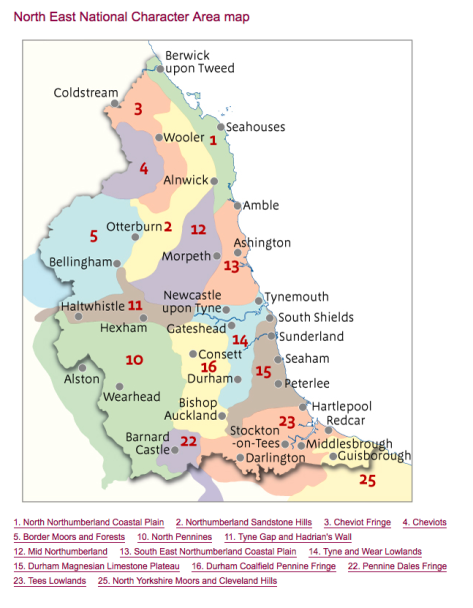

Ultimately this kind of analysis produces very limited data and is concerned with categorisation of space through a series of typologies. These are produced by Natural England as National Character Areas, and divide England into 159 distinct natural areas. Each is defined by a unique combination of landscape, biodiversity, geodiversity and cultural and economic activity. Their boundaries follow natural lines in the landscape rather than administrative boundaries, making them a supposed good decision making framework for the natural environment.

So the five regions that I’m concentrating on can be defined through the following character types

I am happy to admit that they do have their merits, but the point I, and others are trying to make is that no one method of data collection is correct, in fact to even think of it as quantifiable data is wrong, these are living breathing places. Biologist Ludwig von Bertalanffy stated in his book General Systems Theory (1968) ‘complex phenomena cannot be reduced to the discrete properties of the various parts, but must be inderstood according to the arrangement of and the relations between the parts that create a whole. It is the particular organisation that determines the system, rather than it’s discreet parts.’

The French have a term in wine making to describe the complex land properties that go into making wines, that I first came across in 2006 on the BBC’s “Oz and James’s Big Wine Adventure”,

‘Terroir’, the complete natural environment in which a particular wine is produced, including factors such as the soil, topography, and climate. This is often described as Gout de terroir,” which can roughly translate to “taste of the soil,” “taste of the earth” and “sense of place”. It defines a sensory profile, in aroma, taste and tactile sensation that is common to wines grown in the same terroir. To the French, terroir includes the soil, the climate and topography, three conditions that are inseparable.

It got me thinking that could this word be adapted from complex Sense of Place system to another, does an Urban Terroir exist. Some research lead me to a few blog posts on the issue.

‘Terroir’ is not a word to be found in a Dictionary of Human Geography, but geographer Tim Unwin (2012) locates the notion of terroir “at the heart of Geography”. A recent article from The New York Times entitled ‘Vive le Terroir’ reappeared in the International Herald Tribune as ‘A sense of place that defies globalization’. The narrative introduces a family who reside in the rural village of Castelnau de Montmiral, South West France. It explains the family’s deep and emotional connection to the land (Jérôme is a farmer), to the extent that one “knows every inch, every stone, and which parcels are for what”. It describes terroir. The article defines terroir as a concept “almost untranslatable, combining soil, weather, region and notions of authenticity, of genuineness and particularity – of roots, and home – in contrast to globalized products designed to taste the same everywhere”. The elements of soil, weather and region are important here, but the quotation also captures notions that are keenly geographical: roots and home (dwelling perhaps), as well as authenticity and genuineness. The ideas also capture a sense of knowing a place through practice and performance, as well as debates that examine local and global geographies of food production and consumption. The idea of terroir then, is not all that distant from geographical concepts, and may be useful as a tool for capturing a notion more deeply in qualitative or ethnographic research at the micro-level.

Knowing ‘Terroir’: a Sense of Place, Fiona Ferbrache

It is therefore an important idea to use to interrogate the urban environment and a means to discuss the very complex factors that have gone into forming the system as we experience it.

The geography, climate, history and structure of a place impart special meaning on a city. Perhaps most closely linked to the structure, scale and density that make up a spaces’ urban fabric, urban terroir refers to the elements that make up the conditions of our urban spaces. Thus, the feeling of New York City’s is distinct from that of Boston; just as being in Denver feels different from being in Austin.

Another way of looking at terroir is the parts of a city we can influence. Just as a farmer carefully nurtures and cultivates his or her soil, a city can influence its structure and history. Indeed urban terroir posits human cultivation, and cultivation in an urban sense is how a city becomes “our space.”

What gives terroir importance compared to words like ‘density’ or ‘fabric’ is its holistic nature. Urban terroir explicitly includes both humanity and nature and we cannot treat it unconnected from either. Indeed, each is intrinsic to terroir and the reason we cultivate it. Simply focusing on static features such as structure and scale lack this holistic connotation.

While the built form of the city can be static, or dead, its terroir is constantly evolving. As with all living things, terroir is subject to both discrete human intervention and to larger economic and climatic patterns as well as the relationship these factors form. As a mix of the found and the cultivated, urban terroir can be improved, revived, diminished, and even destroyed. Whatever affects it—such as scale—becomes part of the terroir, nurtured both for its own sake and for what it can give to what we want to achieve and to sustain in our cities.

Urban Terroir: The Qualities of a City, Yuri Artibise

As with all things, a sense of Place is a subjective idea, experience (of a place) is personal and depends on the individual personal characteristics, just like Place we are all a complex system informed by similar factors. Take an idea like experiencing a colour, I am colour blind my experiences of red is probably very different to someone else’s, but I know it’s red because that is what I have been told. But then the same applies to the resulting experience of your representations (the curated artwork etc.). Your reading will be coloured by your experiences. All you can do is produce your reading and then let the world respond to it. There is no right and wrong answer, the same, as ultimately you can’t map the character of a location.

To use a ham-fisted analogy, the idea of Place suddenly exhibits some of the basic characteristics of quantum mechanics, were things can exist in multiple states simultaneously, this is often explained with the idea of Shroedinger’s Cat. In the hypothetical experiment, which the physicist devised in 1935, a cat is placed in a sealed box along with a radioactive sample, a Geiger counter and a bottle of poison. If the Geiger counter detects that the radioactive material has decayed, it will trigger the smashing of the bottle of poison and the cat will be killed. Quantum mechanics suggests the radioactive material can have simultaneously decayed and not decayed in the sealed environment, then it follows the cat too is both alive and dead until the box is opened. Up until the point of observation it exists in multiple states, but once observed becomes a fix entity. Our idea of Place is such a complex system that it exists in multiple states/ readings, until observed by an individual, at which point it becomes an entity but just for that individual at that time. This is fine as long as we are aware there is no such thing as objectivity in art, only the individuals curated reading.

If we think of the French concept of terrior being a process in which physical characteristics act on plants, whilst this can be experienced subjectively as a flavour, that flavour will be subject to an individuals variations of palate and likes or dislike of certain aspects.

Are people, and places like plants? Are these complex systems growing, absorbing, being shaped by and then in turn shaping their environment in this way?

Terroir is an evolving context, subject to human intervention and to the vicissitudes of nature in a larger sense. It evolves, but the pace of evolution of its different elements can vary radically. As a mix of the found and the cultivated, terroir can be improved, revived, diminished, and even destroyed.

We use words like structure, scale, density, and fabric to describe the urban context, but these are all elements of something larger. By calling this “something larger” terroir, we raise the possibility of cultivation, but against a deeper background—the regional ecosystem in which a city is situated. Terroir could also be said to be that part of nature we can influence. Thus its boundaries are potentially vast. Exurbia* (read Subtopian Edgeland), the embodiment of our economically and culturally divided society, is also a byproduct of a cultivation strategy that treats social displacement in its different forms as an externality. The question of who cultivates, and why, is as legitimate for city making as it is for farming, fishing, or forestry.

John J. Parman

*(Sociology) US the region outside the suburbs of a city, consisting of residential areas exurbs that are occupied predominantly by rich commuters exurbanites